An introduction to nudging

We are living in a world that is increasingly shaped by technology and marketing, which means that our daily decision-making is often influenced by subtle cues we may not even be aware of. Nudging is a concept that has its roots in behavioural economics and psychology and involves using subtle, non-coercive interventions to influence and guide people's choices and behaviours towards desired outcomes. Rather than forcing or restricting people's choices, nudges make it easier for individuals to make decisions that are in their best interest (e.g., will positively influence their health/lifestyle). Nudges can take a number of different forms from default settings, priming cues in visuals, or choices being framed in a specific way. When used the right way, nudging can be extremely helpful for getting people to behave in prosocial or healthy ways, like saving money, eating healthier, or going greener with their energy use.

So what's all this about a darker side to nudging?

Nudging has gained popularity in policymaking, marketing, and various areas of public and private life as a way to promote positive behaviours and improve decision-making. When used ethically and transparently, nudging can be a powerful tool for facilitating better choices and outcomes for individuals and society as a whole.

Here at Social Change, we're used to talking about and researching 'nudging for social good' such as encouraging healthier eating or exercise behaviours, however, there is also a darker side to nudging. Whilst positive nudges prompt people towards engaging in behaviours that are likely to improve their health or quality of life, dark nudges exploit the principles of behavioural economics to manipulate people into making choices that may not be in their best interest. In this blog, we'll be delving into the darkness and exploring where these types of nudges tend to be used and how to avoid being caught out by them.

Key principles of nudging for social good

Richard Thaler, who co-authored the bestselling book “Nudge”, published in 2008, outlined three key principles of nudging. These centre around the following concepts:

1. Transparency: all nudges should be transparent and not misleading.

2. Autonomy and ease: people should be easily able to opt out of the nudge.

3. Ethical/prosocial: the behaviour the nudge is promoting/prompting should be in the best interest of those receiving it.

Unsurprisingly, 'dark nudges' go against the first fundamental principle of nudging to 'never be misleading', and very often go against all three of these principles. More often that not, they are deceptive, extremely difficult to opt-out of, and more focused on nudging us towards buying a product that benefits the 'nudger' far more than it would the person being nudged. For example, the alcohol industry has been criticised in recent years for using dark nudges in the form of mixed messaging, supposedly about 'responsible drinking' but actually using social norms to present drinking as something 'lots of people are doing' which can cause people not to acknowledge their potentially problematic or harmful drinking behaviours.

Let's explore some other classic examples of dark nudges that are frequently employed in our modern world...

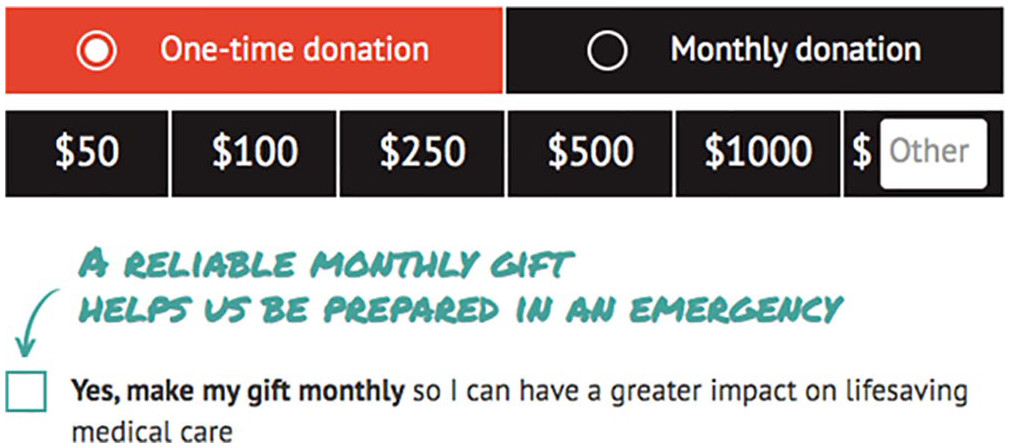

Charity donation/confirm shaming

Have you ever been about to pay for something using a card machine and it asks if you'd like to donate to charity? Well, dark nudges can be used here to provoke feelings of guilt or social pressure by framing the choice you are about to make in a way that makes not donating to charity seem utterly wrong, or frowned upon and shameful. An example would be adding a statement to the 'No' button or option such as "No - I don't care about charity". This is known as 'confirm shaming'. In contrast to these brands and companies who might confirm shaming to boost donations, more ethically-conscious organisations tend to showcase the benefits of donations, for example showing a person what their donation could contribute towards, and its impact on the people who receive it.

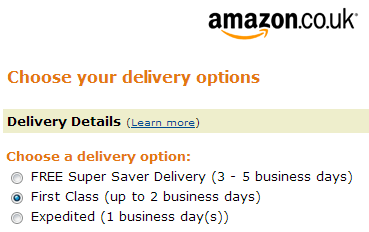

Hidden costs

Picture this. You're unwinding after the working day, and decide to do some online shopping. You see a product you love the look of, at a pretty impressive price (at least, on the face of it). You think okay, I'm interested. So you proceed to click through to the product page, add the item to your shopping basket and proceed to checkout. Just as you're getting ready to fill out your delivery and card details, you clock that your 'basket total' is considerably higher. Suddenly, you realise there's a hefty delivery charge and VAT hadn't yet been added. Sometimes, this information is deliberately obscured or not prominently disclosed until the last step, to reduce the likelihood of you clicking off and deciding not to make the purchase. Once they reach this point, some customers may feel compelled to go ahead with the purchase, even if they're not entirely comfortable with the new, higher price.

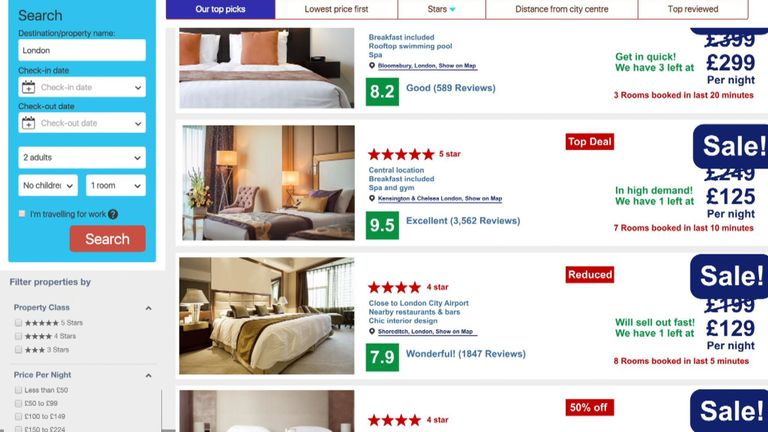

Scarcity tactics

Scarcity mindset refers to when we think something is in short or limited supply and this makes us want it more. Dark nudges can tap into this mindset by presenting us by making us believe that something is available for a short time only and must be purchased instantly. One very common example of a scarcity tactic is limited quantity, whereby products will be advertised as 'only 2 left in stock' or you'll be told an item is in 'X number of people's baskets', making you think that there is a limited supply of what you're interested in, prompting a sense of urgency to secure your booking or purchase. Another is flash sales, those 'blink and you'll miss them' sales where products get a temporary price cut, nudging people to make quick decisions and grab those sweet, discounted deals while they last.

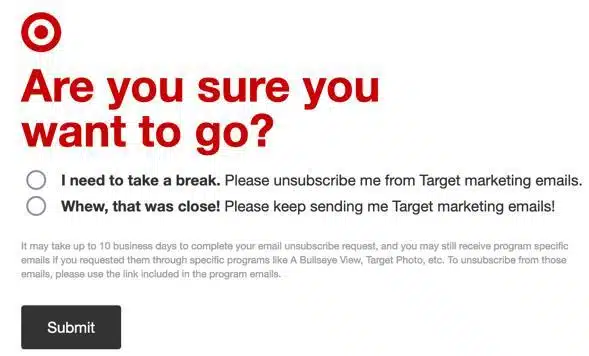

Trying to quit subscriptions and memberships

Ever tried to unsubscribe from marketing emails or car insurance expecting it to be a two-minute job but you're still sat clicking through pages of promotion 10 minutes later and starting to feel somewhat irritated? If so, you're not alone. Many businesses and marketers use dark nudges associated with unsubscribing that make it challenging -and at times downright mind-boggling- to successfully cancel a membership or unsubscribe from offers or emails. This goes against one of the core frameworks for behaviour change, the EAST framework which proposes that in order to support behaviour change, completing a behaviour must be made easy, attractive, social and timely. Dark nudges that make you click through 10 different pages or use deceptive language to confuse you and ultimately give up on your quest to unsubscribe, actively make it harder for you to complete your desired behaviour.

How can we avoid being influenced by dark nudges?

Nudges are subtle and covert in nature, so it's not always easy to spot them, but the more aware you are of the different types that exist, the more able you will be to make informed choices with autonomy. Recognising dark nudges is the first step towards regaining control. By understanding the psychology behind these tactics and learning to spot them, we become better equipped to make decisions that truly reflect our preferences and values. Transparency, awareness, and scepticism are our greatest allies in this endeavour.

Moreover, we should demand ethical conduct from businesses, organisations, and policymakers. We have the right to transparency, fairness, and the freedom to make choices that genuinely serve our best interests. It's up to us, as consumers and citizens, to hold those who employ dark nudges accountable for their actions.

In a world where the boundaries between persuasion and manipulation blur, our ability to protect our autonomy is paramount. By shining a light on the shadows of dark nudging and arming ourselves with knowledge, we pave the way for a future where our choices truly belong to us. It's a future where our decisions are not made by others for us, and are instead, a reflection of our authentic selves.